In Decemer, Venezuela’s president announced a series of measures and legislation to formalize the country’s possession of the oil-rich Essequibo region in Guyana, which he argues was stolen from Venezuela when the border was drawn more than a century ago. Venezuela has instructed the state’s oil and gas agencies to immediately grant operating licenses to explore and exploit oil, gas and mines in the Essequibo region, giving companies already operating in the area three months to leave. Amerindian communities in Guyana have raised concerns that Venezuela’s takeover may threaten decades-long battles for recognition of their customary lands and, in the process, endanger the region’s rich biodiversity. In December, the Venezuelan government launched a series of measures and legislation to cement the country’s annexation of Guyana’s oil and mineral-rich Essequibo region. This is prompting fears among dozens of Amerindian communities that the conflict may threaten ongoing efforts to legally recognize their collective territorial lands or undermine their land titles in this Amazon region.

According to Venezuela’s National Electoral Council, 90% of Venezuelans voted in favor of ownership over Essequibo in a Dec. 3 referendum called by the president in which fewer than half of voters cast their ballots — a result widely criticized by international analysts. The dispute between the two countries over the territory, an area the size of Greece, dates back to 1899 when an international tribunal of arbitration drew the border between them. However, the Venezuelan government states that the dispute began much earlier.

Amerindian toshaos, or village chiefs, in Essequibo fear that a drastic shift in control of natural resources in this large belt of tropical forests may threaten their traditional lands. All five chiefs told Mongabay they are also worried about their safety in the case of an invasion, a concern that extends within the villages. The Amerindian Peoples Association (APA), a Guyanese NGO, told Mongabay that some families have already moved away from their villages in search of security.

But Faye Stewart, a representative of the APA, said that while the threat is real, immediately fleeing lands is mostly due to a lack of access to credible information from the authorities that “stirred up a lot of unnecessary reactions.”

Essequibo River flanked by tropical forests. Amerindian toshaos, or village chiefs, in Essequibo fear that a drastic shift in control of natural resources in this large belt of tropical forests may threaten their traditional lands. Image by Dan Lundberg via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Initially, there was an information blackout from the government while misleading information was spread on TikTok, Steward said, contributing to tension and fear.

On Dec. 29, a British warship arrived in Guyana to conduct training exercises with Guyana’s military. In response, the Venezuelan Armed Forces sent more than 5,600 troops to join a “defensive” operation near the Guyana border. Brazil’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has since expressed concerns about the situation and urged the two South American countries to remain committed to the Argyle Declaration, a bilateral agreement signed in mid-December, when both parties promised to navigate the dispute through nonviolent means.

“I’ve been told that these aggressions have happened even worse in the past, and it’s usually something that we see happening a lot around election time,” said Stewart, mulling over the possibility of an invasion. “But I know it’s different now because of Guyana’s newfound [oil] wealth.”

Guyana map with the conflict areas marked out. Image by SurinameCentral via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Amerindian land rights under question

Romario Hastings, a resident of Kako village in the Upper Mazaruni district, is among more than 85,000 Amerindian peoples living in Guyana today. Nine different groups, which include the Akawaio, Arawak, Arecuna, Carib, Macushi, Patamona, Wai-Wai, Wapichan and Warao peoples, are settled across the country’s 10 regions.

In Guyana, more than 100 Amerindian communities hold absolute, unconditional and collective titles to the land they occupy and use. “If you look up Amerindian land titles in Guyana, you will find that the majority of them are within the Essequibo region,” Romario Hastings told Mongabay. “If [President Nicolás] Maduro has his way, it will jeopardize the steps we have already taken as Indigenous peoples, which have been years and years of struggle.”

According to Hastings, the fact that Maduro does not recognize international law and the international process in the dispute leaves him with huge doubts the president would recognize their Indigenous ancestral lands.

Officials from Venezuela’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not comment on the land rights and future of Amerindian communities living in Essequibo.

According to Graham Atkinson, a representative of the APA, land titling in Guyana has been slow. In 2013, the Ministry of Amerindian Affairs received $10.7 million from the Guyana REDD+ Investment Fund to facilitate and fast-track the Amerindian land titling process. This project, which is known as the Amerindian Land Titling Project, was scheduled to close in 2016 but was extended from 2016 to 2018 and again from 2019 to 2024, as only 20 demarcations out of 68 cases had been completed.

“Guyana has had this long-standing issue of not fully recognizing Indigenous people’s territorial lands,” Atkinson told Mongabay. “It’s still an ongoing battle, and so this whole issue of another country annexing part of the country of Guyana will be very detrimental.”

Some communities are locked in legal battles with the Guyanese government and don’t want their case switching hands.

In 1998, the Kako and five other Amerindian villages from the Upper Mazaruni district took the Guyanese government to court because they were dissatisfied with the land title granted to them in 1991. After a 24-year legal battle, in 2022, the judge ruled that the villagers do not have “exclusive right” to the lands they requested, despite evidence that their people had lived there for more than 2,000 years, because non-Amerindians were also settled there. The Upper Mazaruni District Council (UMDC) has since filed an appeal.

“If Maduro should have his way, that will affect our case, which would have serious implications on our lives as a people,” said Hastings, another toshao of Kako Village and Chairman of the UMDC.

A small Amerindian village in central Guyana. Image by David Stanley via Flickr (CC BY 2.0).

Amerindians in a boat on Kamuni river. Image by Carsten ten Brink via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Oil and riches

For decades, more than 50% of the Guyanese population lived below the poverty line, but in 2015, when U.S. oil giant ExxonMobil discovered an estimated 11 billion barrels of crude oil deposits just off the coast of Essequibo, its economic landscape underwent a drastic transformation. Commercial drilling started in 2019 and the Guyanese economy quickly tripled in size, from one of the lowest GDPs per capita in Latin America and the Caribbean in the early ‘90s to fourth-highest, behind the U.S., Canada and the Bahamas. According to the International Monetary Fund, it is the fastest growth rate anywhere in the world. The country also holds large quantities of gold, diamond and bauxite.

Meanwhile, more than 7.7 million Venezuelans have fled their country since 2015 as a result of economic and political turmoil. The country is experiencing a humanitarian crisis that has condemned three-quarters of the population to extreme poverty. In 2020, starved of adequate investment and maintenance, oil exports dropped to a 75-year low and, according to shipping and tracking data, despite the easing of U.S. sanctions, exports did not rise as much as expected last year.

“The Essequibo region is of interest due to being rich in natural resources, including fertile land and very lucrative oil reserves offshore,” Matheus de Freitas Cecílio, a researcher from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, told Mongabay. “The most recent discoveries of oil reserves put Guyana as one of the countries with the most promising economic growth trajectory in the next few years.”

Maduro has laid out his plans to explore oil, gas and minerals in Essequibo, where dozens of Amerindian villages sit. He instructed the state-owned oil company Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) and decentralized state-owned minerals company Corporación Venezolana de Guayana (CVG) to immediately “grant operating licenses for the exploration and exploitation of oil, gas and mines.”

He also proposed a special law to prohibit oil concessions granted by Guyana in Essequibo to be delimited. “We are giving three months to the companies that are exploiting resources there without Venezuelan permission to comply with the law,” Maduro said.

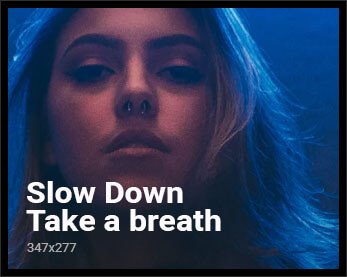

A gold mine in the middle of the forest in Guyana, which leads to damages to Amerindian community resources, increase human conflict and pollution of rivers with sediment and mercury. Image by Allan Hopkins via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

According to a report published by the environmental organization Observatory of Political Ecology of Venezuela, the PDVSA’s aging infrastructure and the country’s weak environmental regulations was responsible for the country’s rise in oil spills and gas leaks in 2022. The spills caused pollution that threatened marine ecosystems and led to the deaths of seabirds, fish and other marine life. As the national economy collapses, the state-owned company has cut down on maintenance and supervision, particularly in Lake Maracaibo, where many pipelines and facilities are more than 50 years old.

Because the majority of these oil blocks are found in Guyana’s coastal waters and do not directly impact Amerindian lands mainly located inland, oil drilling has not yet posed big issues for land rights in Essequibo.

However, Maduro’s interest in mineral exploration and exploitation inland has a possibility of directly impacting Amerindian lands.

Guyana’s own mining interests and activities in the region have already been an issue for these communities in the past, although many Amerindians are also involved in small-scale mining operations. Despite policies and contracts to secure consultation, communities continue to run into land disputes with the government and companies that prospect on their titled lands. When mining has occurred in or nearby communities, some have suffered from river and drinking-water contamination by mercury used in the mining process and a decline of fishing and game.

“The [Guyanese] government’s plan is to exploit resources to develop the country … but the government proposes plans and implements them without our full participation, and that has been a problem,” said Mario Hastings, the toshao of Kako village. “They continue to grant concessions, forest concessions and mining concessions, when we do not agree.”

Amerindian communities in Essequibo say a new wave of oil and gas concessions without recognition of their Guyanese land titles will have a huge impact on the environment. Lennox Percy, toshao of Paruima village in the Cuyuni-Mazaruni region, told Mongabay that his community has no interest in mining. “Our way of living is sustainable,” he said. “We don’t want that kind of industry in this area.”

Both PDVSA and CVG did not respond to requests for comment. Neither did officials from Guyana’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Banner image: An Amerindian guide paddles his canoe up the Burro Burro River, Guyana. Image by David Stanley via Flickr (CC BY 2.0).

Guyanese project to bolster Indigenous land rights draws funding — and flak

Related listening from Mongabay’s podcast: A conversation with Cultural Survival’s Daisee Francour and The Oakland Institute’s Anuradha Mittal about their thoughts on Indigenous land rights and the global push for land privatization. Listen here:

Citation:

Venezuela FAA118/119 Tropical Forest and Biodiversity Analysis. (2022). Retrieved from USAID website: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00ZKHH.pdf

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

Correction (18 January 2024): Mario Hastings is the toshao (chief) of Kako village, not Romario Hastings, who is a resident. Mongabay regrets the error.

Biodiversity, Conflict, Conservation, Education, Environment, Environmental Education, Environmental Law, Environmental Politics, Funding, Government, Indigenous Communities, Indigenous Peoples, Indigenous Rights, Land Conflict, Land Rights, Law, Mining, Oil, Oil Drilling, Politics, Resource Conflict, Tropical Deforestation, Tropical Forests

Guyana, South America, Venezuela